Fall 2021

Talent Newsletter

Talent Newsletter

In this issue... Director's Message: What We've Learned About Gifted Education and Talent Development | The Evolution of Gifted Education and Talent Development | Role of Universities in Talent Development | Implications for Practice of the Talent Development Approach

In this issue of Talent, we take a close look at traditional definitions of giftedness and juxtapose them with the talent development framework that has always characterized CTD, reflecting on changing times and what we have discovered about learning and human development. To provide context for this discussion, I spoke with Center for Talent Development (CTD) founder Joyce VanTassel-Baska about the evolution of these models, how they impact the services and educational methodologies employed in the classroom, and the future of the field of gifted education.

the talent development framework that has always characterized CTD, reflecting on changing times and what we have discovered about learning and human development. To provide context for this discussion, I spoke with Center for Talent Development (CTD) founder Joyce VanTassel-Baska about the evolution of these models, how they impact the services and educational methodologies employed in the classroom, and the future of the field of gifted education.

This issue also addresses how CTD works collaboratively within Northwestern University’s School of Education and Social Policy (SESP) to expand our reach and unlock access and potential at every educational level.

Examining CTD’s forty-year history of talent development plays an important role in defining our vision for the future. I hope these insights will serve our readers as we work to advocate for advanced learners.

Paula Olszewski-Kubilius

Director, Center for Talent Development

Center for Talent Development (CTD) founding director Joyce VanTassel-Baska has dedicated her fifty-year career to publishing research, advocating for policy, and developing curriculum to support advanced learners. In 2011, she received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Mensa Foundation for her vast contributions to the field of education. For this issue of Talent, CTD director Dr. Paula Olszewski-Kubilius and Dr. VanTassel-Baska, unpack the evolution of gifted education and the talent development model, current challenges in the field of gifted education, and the essential elements needed for academic talent development programs to thrive.

Center for Talent Development (CTD) founding director Joyce VanTassel-Baska has dedicated her fifty-year career to publishing research, advocating for policy, and developing curriculum to support advanced learners. In 2011, she received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Mensa Foundation for her vast contributions to the field of education. For this issue of Talent, CTD director Dr. Paula Olszewski-Kubilius and Dr. VanTassel-Baska, unpack the evolution of gifted education and the talent development model, current challenges in the field of gifted education, and the essential elements needed for academic talent development programs to thrive.

Early research on gifted children centered on finding individuals with exceptionally high IQs. By focusing on outliers, including prodigies and twice exceptional students, a mythology of the gifted child as qualitatively and psychologically different emerged.

“In kids with very high IQ, their development may be uneven, and psychological characteristics may manifest in ways they don't in typical gifted learners,” notes VanTassel-Baska. These traits became integrated with perceptions of gifted individuals generally. “Psychological characteristics got amplified at the expense of learning characteristics that were disregarded as unimportant or not a central part of who this person really was”, says VanTassel-Baska. Research has since shown that gifted learners are not a homogeneous group, that IQ has limitations in terms of measuring intelligence, and that psychosocial skills like motivation and creativity need to be taken into account when discussing giftedness and high achievement.

perceptions of gifted individuals generally. “Psychological characteristics got amplified at the expense of learning characteristics that were disregarded as unimportant or not a central part of who this person really was”, says VanTassel-Baska. Research has since shown that gifted learners are not a homogeneous group, that IQ has limitations in terms of measuring intelligence, and that psychosocial skills like motivation and creativity need to be taken into account when discussing giftedness and high achievement.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · The Role of Talent Search in Gifted Education

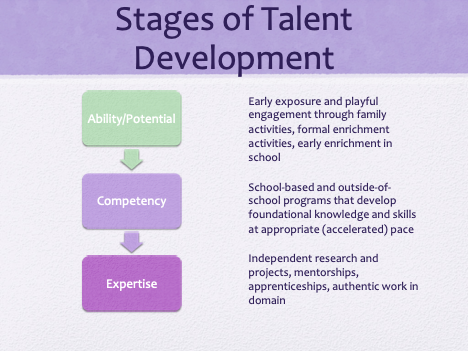

A shift toward a long-term approach, more inclusive of the differences among students, and focusing more on their development rather than innate ability, resulted in the talent development model slowly gaining favor within gifted education. Dr. Olszewski-Kubilius has dedicated her career to researching talent development, exploring its implications for gifted education specifically and education generally, and applying her findings in the programs and services provided at the Center for Talent Development. She and her colleagues, Drs. Rena Subotnik and Frank Worrell, produced a seminal work in the field, titled Rethinking Giftedness and Gifted Education: A Proposed Direction Forward Based on Psychological Science.

Dr. VanTassel-Baska embraced this view forty years ago when founding the Center for Talent Development, as the name suggests. Despite the tension between acknowledging inherent abilities and a malleable, developmental perspective on ability, VanTassel-Baska doesn’t see talent development as conflicting with gifted education, but rather broadening it: “I saw it as a way to explore new areas, to consider groups of students that had not been identified, and to take a lifespan development approach to gifted education in a way that had not been done in the past.”

"If kids don't have the opportunities or the context in which to experience a particular field, or to express their abilities or have them nurtured, their potential and talent might go unnoticed." -Dr. Paula Olszewski-Kubilius

Reflecting on differences within the field between the talent development approach and the traditional gifted approach, Olszewski-Kubilius points to a disconnect between current practice and new conceptual frameworks. The field has been largely focused on the identification of students as gifted, and states have laws and procedures reflecting that, rather than on the development of giftedness through programming and support. Conceptually, CTD has always been about talent development. "We do care about finding talent (identification), but we're also very focused on the talent development enterprise (programming), which to me is the more primary aspect.”

Olszewski-Kubilius draws another distinction in the talent development model’s recognition that the expression of giftedness or talent is very contextual. “If kids don't have the opportunities or the context in which to experience a particular field, or to express their abilities or have them nurtured, their potential and talent might go unnoticed,” notes Olszewski-Kubilius. “It makes giftedness more complex and challenging to identify, but gives a more valid picture of the reality of talent development .”

The evolution of gifted education research and talent development programs resonates in the issues at stake today. For many years, gifted children continued to be portrayed as unique as a means to justify services to meet their different needs. “Today we're in a different context where the issue of someone being more special than others is not going to work, and really never did,” notes Olszewski-Kubilius.

The field of gifted and talented education is at a critical juncture. In public school systems across the United States, students experiencing poverty, students with identified disabilities, and students of color have been placed in gifted programs at much lower rates. These inequities are driving a debate over whether to broaden access to services, for example by increasing gifted programming in low-income neighborhoods and schools, or to eliminate services entirely, particularly self-contained or highly selective programs in public schools, often leaving classroom teachers with the difficult task of differentiating for students with a large range of skills, knowledge, and abilities.

Educational leaders are also facing quandaries regarding the equitable identification of academic talents. Those in favor of eliminating entrance exams and standardized tests like the SAT® argue they are biased, predict performance poorly, or present financial and preparatory barriers discriminating against disadvantaged students. Others contend that reforming practices around administering these tests, for example requiring all high school students to be given the ACT® or SAT free of charge during school hours, would help students more than eliminating a relatively objective admissions criterion.

When it comes to the talent development approach, and early access to opportunities, VanTassel-Baska worries that eliminating the SAT and other tests without an evidence-based, effective replacement model “will hurt the very students that we want to serve the most, because many students from low income backgrounds, many students of color, do very well on those kinds of tests. And now they will have no chance to be identified in that particular way.” It is important to have multiple pathways to demonstrate ability, achievement, and exceptional potential. Tests are one tool that can be beneficial when used properly.

“The field is in a difficult place,” emphasizes VanTassel-Baska. “I see a period of retrenchment, in which many places are spending a lot of time being reactive in terms of reconstituting their identification systems predominantly; in some instances, cutting back on programs; and in many ways, causing gifted education to be a diminished enterprise.”

Dr. Olszewski-Kubilius points to talent development, as a field of research, as having the potential to take educational practice toward a more equitable system that maximizes the potential of young people, focusing on their strengths. “Unfortunately, the way gifted models have been traditionally implemented has had the opposite result. But, if we really focus on talent development, which puts a greater emphasis on early potential and developing it through opportunities for enrichment and exploration of interests supported by rigorous curriculum, I believe we could contribute to tackling the essential problem in education, which is opportunity gaps that underlie achievement gaps.”

Olszewski-Kubilius suggests early intervention, providing enrichment opportunities with open enrollment for younger students in programs such as Head Start, and utilizing performance-based assessments, for example identifying talent through a portfolio, as strategies for addressing opportunity gaps.

“Gifted and talented is a field that's still misunderstood in terms of the conceptual aspects, as well as the translation into day-to-day practice,” notes VanTassel-Baska. “The gap in understanding the concepts related to giftedness interfere greatly with how it's operationalized in schools and in other settings.”

“Another challenge for our field is that many of the programs that have been successful, particularly at different ways of identifying and/or serving underrepresented kids, are only discussed in research articles and aren’t influencing practice in the classroom.” Dr. Joyce VanTassel Baska

VanTassel-Baska and Olszewski-Kubilius identify research-to-practice gaps and changes in administration as challenges to implementing gifted and talented programs in K-12 classrooms. The turnover rate among school administrators—about every five to six years for superintendents and four years for principals—presents obstacles of structural instability in sustaining programs. “Often their goal is to come in and introduce something innovative. Replacing current programming is often a part of that process,” says VanTassel-Baska. “That model is very insidious in terms of building gifted programs and services, especially when new administrators haven’t had anything to do with gifted programs and may be antithetical to them."

“Another challenge for our field is that many of the programs that have been successful, particularly at different ways of identifying and/or serving underrepresented kids, are only discussed in research articles and aren’t influencing practice in the classroom,” says VanTassel-Baska, citing studies on intervention as the most powerful research in the field of gifted education. “The gap between research and practice in education is particularly large in our field,” adds Olszewski-Kubilius. “Part of the problem is that we're marginalized in terms of teacher preparation. Only 18 states require any training in gifted education.”

“The problem with most gifted programming is that it's sort of this add-on,” notes Olszewski-Kubilius. “The idea is to have it in the school, but not have it overlap with or affect anything else that's going on in the school. That's just not realistic; it's not really part of the curriculum.”

Olszewski-Kubilius advises administrators struggling with their gifted education services, and trying to figure out what it means to shift to a talent development model, approach it from an equity lens. As part of their goal to serve all students well, schools should provide more enrichment to all students, personalize education whenever possible, and help all students grow regardless of where they start.

“There's greater recognition right now that education would be more valuable or more impactful if it was more personalized. That’s long been a theme in gifted education, with the idea of differentiation,” notes Olszewski-Kubilius.

Olszewski-Kubilius advises educators to aim high and try to get more kids to that level, as opposed to taking a remedial approach that underserves many students. Focusing on areas of strength while scaffolding to help students with uneven skill development will help them maintain the confidence and self-esteem they need to be successful learners while also maintaining their interest. A student who loves learning about outer space, for example, may be more motivated to hone their writing skills while engaged in a science-related project. “Kids will find more meaning and be motivated to reach when engaged in subject matter that’s exciting to them.”

We don’t want young people to be ambivalent about their talents or the things that they can achieve. Cultivating exceptional ability requires environments that utilize students’ strengths, nurture their potential in their domains of talent, and prepare them for the future—whatever they want that future to be.

"Northwestern isn’t just a compass point on a map. Here, it’s a mindset. A Northwestern Direction is a journey that each one of us creates and defines as our own. There’s always a new adventure, a new idea, and a new discovery—no matter what path you pursue." This is one of Northwestern's core messages, and it is fully aligned with CTD's talent development pathways approach.

a new discovery—no matter what path you pursue." This is one of Northwestern's core messages, and it is fully aligned with CTD's talent development pathways approach.

Top universities play a vital role in examining, creating, and facilitating college access and helping students pursue their passions. Northwestern has embraced this charge and used it as a catalyst for social mobility. At the Center for Talent Development (CTD), here within the School of Education and Social Policy (SESP), we’re a leading force for this type of work – serving as the front porch for young people and families who come to learn on our campuses for the first time. As Joyce VanTassel-Baska points out, it provides a structure for talent to be mobilized and a way for students to engage early.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · The Importance of Universities and Centers in Talent Development

We know from research that nothing stops a talented young student from attending a top university more than the feeling that they don’t “belong”. This is especially true for underrepresented students and students from low-income households. By reaching talented young people at an early age, before they begin believing these stereotypes, we are positively impacting their educational outcomes and future.

At SESP, we know that every single human being has exceptional assets, and our goal is to help unlock those abilities. CTD’s focus on identifying and developing the talents of young learners creates opportunities for these students to pursue their interests and passions, gain exposure to college and career, and discover a home within this community of bright learners and future leaders.